Please select a partnership to see additional information:

2.26 Injuries in Babies and Children under 2 years of age

Contents

- Practice Guidance for Assessment, Management and Referral(Jump to)

- Definitions/Scope of Guidance(Jump to)

- Introduction(Jump to)

- What to do if any type of injury (including bruises) are seen on a non-mobile child/baby or there are concerns about non-accidental injury in a child under 2 years(Jump to)

- Responsibility of Children’s Services(Jump to)

- Responsibility of On call Paediatrician(Jump to)

- References/Resources(Jump to)

The aim of this guidance is to support practitioners by providing guidance about the management and referral of babies and children under the age of 2 years, particularly those who are not yet independently mobile, who have presented with an injury.

It does not replace the process to be followed once a referral to Children’s Services has been made.

- Not Independently Mobile: A child of any age who is not yet crawling, bottom shuffling, pulling to stand, cruising or walking independently. It should be noted that this guidance applies to all babies under the age of two years. The guidance also applies to older immobile children, for example immobility due to disability/illness.

- Bruising/Suspicious marks: It is not always easy to identify with certainty a skin mark as a bruise. Practitioners should take action in line with this guidance if they believe that there is a possibility that the observed skin mark could be a bruise or could be the result of injury or trauma.

- Mobile Children: While accidental and innocent bruising is significantly more common in older mobile children, practitioners are reminded that mobile children who are abused may also present with bruising and suspicious injuries. Mobile children with inflicted bruising may or may not give a disclosure. If appropriate to the practitioner’s role, knowledge, and skills they should seek a satisfactory explanation for all such bruising, and assess its characteristics and distribution, in the context of age and development stage, family and environmental history, to ensure that it is consistent with an innocent explanation. Otherwise, the practitioner should seek supervision and guidance from expert practitioners/Children’s Services. All allegations/disclosures also need to be considered even where no visible bruise. Where there is no credible explanation for a bruise or injury a referral should be made to children’s social care and a CP medical conducted to assess whether it is a NAI resulting from abuse and neglect.

Children under the age of 2 years are at an increased risk of serious physical abuse and are rarely able to communicate the history themselves. Non-inflicted injuries in non-mobile infants are unusual. Children with a disability who are not able to move independently are also at risk of serious physical abuse.

Even small injuries in non-mobile children may be significant and may be a sign that there is another injury that is not visible e.g. fracture in an infant with a small bruise. They may also be a “sentinel injury”; i.e. an injury that, if not recognized as possibly inflicted and acted upon, is associated with later severe or fatal maltreatment. Babies under 6 months are particularly vulnerable to fatal abuse.

It should also be remembered that even when mobile, children under two are rarely involved in activities with speed or height (i.e. which generate high-force impacts): they cannot run at speed and have low standing heights. Also remember that young children require a high level of supervision: multiple injuries in different sites may also be a sign of neglect

Features in the history that raise suspicion of physical abuse include:

- A significant injury where there is no explanation

- An explanation that does not fit with the pattern of injury seen.

- An explanation that does not fit with the motor developmental stage of the child.

- Injuries in infants who are not yet independently mobile.

- An explanation that varies when described by the same or different parents/carers.

- Multiple explanations that are proposed but do not explain the injury sustained

- Delay in seeking medical attention – delayed presentation

- An inappropriate parent or carer response e.g. unconcerned or aggressive.

- A history of inappropriate child response (e.g. didn’t cry, felt no pain)

- Presence of multiple injuries (at one time, or a pattern of injuries over time)

- Child or family known to children’s social care or subject to a Child Protection Plan.

- Previous history of unusual injury/illness e.g. unexplained apnoea (stopping breathing).

- Repeated attendance with injuries that may be due to neglect or abuse.

- Consider child maltreatment if there is an unusual pattern of presentation to and contact with health care workers, or there are frequent presentations or reports of injuries (Child maltreatment: when to suspect maltreatment in under 18s. NICE)

Bruising

Bruising is the commonest presenting feature of physical abuse in children. Reviews of the research conclude that bruising is strongly related to mobility and that bruising in a baby/child who is not yet crawling, and therefore has no independent mobility, is very unusual. While up to 60% of older children who are walking have bruising, it is found in <1% of not independently mobile infants. The younger the child the greater the risk that bruising is non-accidental and the greater potential risk to the child. Bruises are rare in infants and pre-cruisers. Bruises in infants younger than 9 months and who are not yet beginning to ambulate should lead to consideration of abuse or illness as causative (Those who don’t cruise rarely bruise. Sugar, MD et al 1999)

Accidental bruising from everyday falls, trips and slips usually result in a single bruise on a bony prominence over the anterior surface of the body, the most common location being the shins and “facial-T” (forehead, bridge of nose, mouth and point of chin). They may also occur over the occiput or lower back. They are not patterned or petechial in nature. Petechiae are tiny red or purple spots which often get misdiagnosed as a rash.

Inflicted bruises are more likely if:

- Infant is not yet independently mobile

- Bruising on unrelated sides attributed to the same ‘accident’ (for example on both right and left sides, or on front and back of the body, from a ‘fall)

- Patterned, showing a positive or negative image of an implement used (e.g hand slap mark)

- Petechial bruising (pin-point red or purple dots caused by bleeding in the surface layer of skin, which may be scattered or form patterns such as lines)

- Located on protected areas such as the neck, cheek, ear, buttocks, abdomen, upper and mid back, genitalia, posterior thighs, and forearms.

A bruise must never be interpreted in isolation and must always be assessed in the context of medical and social history, developmental stage and explanation given.

Bruising in a child who is not independently mobile in any location is a concern. It is recognised that a small percentage of bruising in non-independently mobile babies and children will have an innocent explanation (including medical causes). This practice guidance should be followed nevertheless because of the difficulty in excluding non-accidental injury.

The briefing from the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel September 2022 recommends, that in all cases of bruising in children who are not independently mobile there is:

- a review by a health professional who has the appropriate expertise to assess the nature and presentation of the bruise, any Associated injuries, and to appraise the circumstances of the presentation including the developmental stage of the child, whether there is any evidence of a medical condition that could have caused or contributed to the bruising, or a plausible explanation for the bruising (this should be;

- a multi-agency discussion to consider any other information on the child and family and any known risks, and to jointly decide whether any further assessment, investigation or action is needed to support the family or protect the child. This multi-agency discussion should always include the health professional who reviewed the child.

Where the question asked of the medical professional is: is this suspicious of inflicted injury?

Then this needs to be answered through a child protection medical assessment and should be reviewed by a Paediatrician. The child should not be presented to a GP or Emergency Department for a child protection medical assessment.

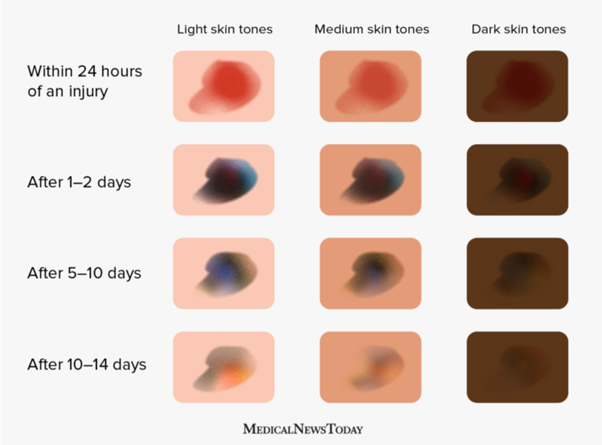

Stages of healing in bruising in infants

Bruise colours depend on factors such as the intensity of an injury, the location on the body, and a infant’s skin tone.

A person may be able to estimate how old a bruise is from its colour. As the body heals and breaks down the haemoglobin, the compound that gives blood its red color, the bruise will change colour. This is a regular part of the healing process.

Skin colour affects the appearance of bruises. A 2013 study suggested that people with medium skin tones may have more red and yellow in their bruises than people with lighter or darker skin tones. Bruises on darker skin tones appear darker and have fewer noticeable colour changes than those on lighter or medium skin tones.

During the healing process, a bruise will usually go through the following colour changes:

- Within 1–2 days, the haemoglobin in the blood changes and the bruise looks bluish-purple or even black.

- After 5–10 days, the bruise looks green or yellow.

- Then, after 10–14 days, it turns yellow-brown or light brown.

Visuals of Colour Stages of a Bruise

Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis (Blue spots/Birth marks)

Blue spots are congenital birthmarks. They are most found in individuals of African or Asian ethnic background including dual heritage children. They are:

- Hyper pigmented skin areas

- Usually seen at birth or early life

- Often familial

- Common in children of Asian/African descent

- Rarer in Caucasians

- Usually bluish/slate-grey in colour

- Usually flat & not raised, swollen, or inflamed.

- Usually round/oval but can be triangular, heart-shaped, or linear.

- Can be single or multiple marks.

- Usually on the lower back/sacrum/buttocks

- Occasionally the spots can appear elsewhere on the body, like the

- shoulder Trunk, extremities (rarer)

- Face or scalp (extremely rare)

- They usually fade with age

How can I tell if it's a bruise or a congenital dermal melanocytosis?

Congenital dermal melanocytosis and bruises do look very similar, and the birthmarks are often mistaken for bruises. However, they are different in a few ways.

Bruises change colour, size and shape over the course of just a few days, while congenital dermal melanocytosis stay the same for many years. Also, congenital dermal melanocytosis are not painful when touched.

Congenital dermal melanocytosis are present from birth.

What to do if you are concerned

Check that the congenital dermal melanocytosis/ blue spot is recorded in the child health records.

If it is not recorded in the child health record inform the health visitor and GP of your observations and seek clarity as to whether the mark has been seen before and recorded on the child’s health records.

If there is no previous record of the blue spot, the possibility of maltreatment must always be considered, and you must follow this protocol for assessment of injuries in non-mobile children.

NICE guideline When to Suspect Child Maltreatment (Clinical Guideline 89, 2009) states that bruising in any child Not Independently Mobile should prompt suspicion of maltreatment.

There is a substantial research base on the significance of bruising in children. http://www.core-info.cardiff.ac.uk/reviews/bruising and Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel paper about bruising to children

A bruise should not be interpreted in isolation and must always be assessed in the context of medical and social history including repeat presentations with similar concerns, developmental stage and appropriate explanation given. A full clinical examination and relevant investigations must be undertaken, following local and national guidance.

Fractures

All suspected fractures require medical assessment.

Accidental fractures in children under 2 years are uncommon, and the greatest risk of abusive fractures are in children under 18 months old.

Fractures which are particularly associated with abusive injury in babies and very young children are rib fractures, metaphyseal fractures, humeral fractures, femoral fractures, (in the absence of major trauma, birth injury or underlying bone disease)

Skull fractures occur in infants by both accidental mechanisms (i.e. dropped) and abusive mechanisms (thrown, hit).

simple Linear fractures are the most common type in both abusive and non-abusive skull fractures.

Skull fractures which are complex, bilateral, or widened are suggestive of abusive injury.

There is some debate about the height threshold for which such injuries occur from a fall; recent studies indicate that such injuries only occur when falling from a height >60cm (Biomechanical characteristics of head injuries from falls in children younger than 18 months. Hughes et al).

Intracranial Head Injuries

Subdural haemorrhage and hypoxic-ischemic injuries are often seen in cases of shaking. Signs can include high pitched scream, new onset fixed down-and-out squint, seizure, loss of consciousness/floppiness, rapid growth in head size, bulging fontanelle.

Urgent medical attention is required.

Burns and scalds / thermal injuries

Burns and scalds are common accidental injuries, resulting from varying degrees of parental inattention, so neglect may have to be considered at presentation. A number involve deliberate abuse. 1-29% have been reported as deliberately inflicted. 70% of accidental burns and scalds in childhood occur in children under 3 years of age with the greatest prevalence being in toddlers between the ages of 12 and 24 months. An estimated 10% are secondary to maltreatment.

All childhood burns must be carefully assessed. The burn may be as a result of neglect or lack of supervision.

Scalds from physical abuse predominate in infants and toddlers:

- Frequently involve immersion injury and affect the hands and feet with clearly demarcated edges (glove and stocking appearance).

- Frequently involve the buttocks and legs.

- Frequently are bilateral and symmetrical

- Any soft tissue area not expected to come into contact with a hot object (e.g. back of hands, soles of feet, back, buttocks) in a child who is not yet independently mobile should automatically raise suspicion.

Abusive contact burns can be singular or multiple and can be found on any part of the body. The site often involves regions of the body that the child is unable to reach themselves. They are often multiple or have a clear demarcation such as an iron burn, unlike accidental burns which are generally single (apart from iron burns).

Typically, intentional cigarette burns are circular lesions and can be found on any part of the body. . They heal to leave circular scars. However, Commercial cigarettes are classically 1cm diameter and indurated (crater-shaped), but own-rolled or cigars can be different sizes. If multiple-burns overlapping they may lack the round shape, or if dragged across skin/child manages to pull away they can be comet-shaped.

Thermal injuries including cold injuries (swollen red hands or feet) with no obvious explanation may be a sign of child maltreatment.

Bites

Human bites with the full mouth leave a ring shape or paired-arc shaped bruise. Teeth impressions may be visible but are not always seen. Partial bites may not leave this characteristic shape. Round bruises with central clearing from impact injuries may be mistaken for bites without individual tooth marks. Human bites rarely break the skin (unlike animal bites)

Any human bite could be abusive and should be fully assessed to differentiate between an adult bite and a child’s bite, ideally by a forensic dentist (see www.bafo.co.uk). Forensic dentists potentially play an important part in the child protection process. If involved early enough, they can take serial photographs and casts of the bite, and possibly retrieve DNA, which can help identify the perpetrator. However, there are fewer than 30 in the UK.

If a doctor or dentist is unable to make immediate contact with a forensic dentist, they should first measure and record the inter-canine distance, then obtain photographs of the suspected bite. The photographic record must include one plain image and a second image that includes a right-angled measuring device beside the mark.

Consider neglect if an animal bite occurs in a child under the age of 2 years, and particularly in a child under 1 who is not independently mobilising.

Other injuries

Bruised lip or torn frenum (small piece of skin between the inside of the upper and lower lip and gum). Any oral injury when an explanation is absent or unsuitable should raise concerns. In infants, forcing the bottle into the mouth can tear the frenum.

Subconjunctival haemorrhage (small bleeds into the whites of the eyes) is a frequent finding in otherwise healthy newborn babies. They should resolve in 10-14 days but sometimes can take a bit longer. They are also thought to occur in infants with prolonged coughing or blood disorders. However 2 studies report their presence in child abuse. NICE guidance suggests child maltreatment if a child has retinal haemorrhages or injury to the eye in the absence of major confirmed trauma or a known medical explanation.

Lacerations, abrasions and scars are not common in children under 1 year of age without a suitable explanation.

Intentional poisoning

A child’s ingestion of tablets, medicines, laxatives, domestic products, alcohol, drugs, and dangerous amounts of salt may not always be due to accidental carelessness. A carer may administer substances like sedatives to a child to keep them quiet at night or may wish to harm the child, or to present the child as ill (fabricated or induced illness).

Symptoms may be extremely variable but may include drowsiness, vomiting, or seizures. Multiple attendances of children in a family with 'accidental ingestions' at an Emergency Department may signify intentional poisoning or at least lack of appropriate parental supervision when neglect may be a factor. 'Double' ingestions are of particular concern.

Suffocation

It may be impossible to differentiate intentional airways obstruction from other causes of unexplained death in infancy. It may present in young infants as:

- Sudden death;

- A well baby with a history of recurrent episodes of apnoea (cessation or suspension of breathing), cyanotic (blue) episodes, recurrent seizures, unexplained or unusual collapse, bleeding from the mouth and nose;

- May be associated with petechiae or subconjunctival haemorrhage

All non-mobile infants and non-mobile children of any age with an injury should be managed in line with the procedures below.

For more information, please refer to Reference/Resources.

All Practitioners – including General Practitioners, school nurses, health visitors, midwives, Allied Health Professional Occupational Health, Physiotherapist, Dietician and Radiographer, nursery staff, children centre workers, education, social workers, and other (non- child health) professionals

- Professionals should refer to the ‘Child Protection Medical Assessment Pathway - Toolkit for Practitioners’ (February 2023). The Toolkit has been developed in partnership between health, social care and police and is aimed at anyone in Birmingham and Solihull who works with and has safeguarding responsibilities for children of any age.

- Should discuss the bruise / injury with the parent /carer and enquire into its explanation, origin, characteristics and detailed documentation of this should be made in the child’s records. At the very least there should be safeguarding supervision on the same day. For non-mobile babies, the default position should be to refer to children’s social care so the decision is made by multi-agency partners.

- The decision to refer to Children's Services and for a potential medical examination should be explained to the parents or carers openly and honestly as a professional duty of care to safeguard children (Childrens Act 1989).

- The responsibility for arranging pre-planned medicals remains with Children’s Services and MASH health nurses. If you have concerns about the personal safety of yourself or other staff or in relation to the safety of the child or their siblings in these situations, you should consider prior to the medical whether a visit to the family should be undertaken jointly with the Police or whether the Police should be present during the medical.

- Should record all discussions, decisions and actions, and confirm your referral to Children’s Services in writing within 48hrs as required within the local threshold for intervention guidance. You may also choose to speak to the Paediatrician who will be doing the medical examination to explain your concerns and ensure they have all the relevant information.

- In the case of newborn infants where bruising may be the result of birth trauma or instrumental delivery, professionals should remain alert to the possibility of physical abuse even in a hospital. In this situation clinicians should take into account the birth history, the degree and continuity of professional supervision and the timing and characteristics of the bruising before coming to any conclusion (reference should be made to the red book or child’s record for further clarification).

- It is particularly important that accurate details of any such bruising should be communicated to the infant’s general practitioner, health visitor and community midwife.

- Where practitioners are uncertain whether bruising is the result of birth injury they should refer immediately to children social care who will then liaise with the on call Paediatrician. If concerns remain a referral to Children’s Services should be made. Wherever possible, the decision to refer should be undertaken jointly with the on call Paediatrician, however this requirement should not prevent an individual professional referring to Children's Services any child with bruising who, in their judgement, may be at risk of child abuse. If a referral is not made, the reason must be documented in detail with the names of the professionals taking this decision.

- Any child who is found to be seriously ill or injured, or in need of urgent treatment or further investigation, should be referred immediately to the Emergency Department (ED).

- The referral to ED should not be delayed where a referral to Children’s Services has not occurred; however, it is the responsibility of the professional first dealing with the case to ensure that, where appropriate, a referral to Children’s Services is made.

- Practitioners should make a referral to Children’s Services without delay, using the Multi-Agency Referral Form/Multi-Agency Contact Form relevant to the local authority area for the child.

- Open cases - when the family already have an allocated social worker, new concerns should be raised with the social worker or team manager with the request that a strategy discussion is arranged.

- A strategy discussion will always be held with representation from Children’s Social Care, Police and Paediatrician to inform further enquiry and action.

It is recognised that a percentage of bruising in children ‘Not Independently Mobile’ will have an innocent explanation (including medical causes). Nevertheless because of the difficulty in excluding non-accidental injury, professionals should always refer to a social worker who will arrange for the child to be examined by a paediatrician.

Babies/Children presenting at Emergency Department (ED)

- ED practitioners should follow their local hospital policy and procedures. If an injury is seen in a non-mobile child a discussion with Children’s Services should occur even if the injury is felt to be accidental to ensure that all available information is used to make that decision. If a referral to Children’s Services is made, staff should be prepared to attend (or nominate a member of the team to attend if they are not on duty) a strategy meeting within 24 hours.

- If a referral is not made, the reason must be documented in detail with the names of the professionals taking this

Children services responsibilities:

- MARF referral form received. MASH social worker begins to review case reported including checking whether the child is previously known

- Partner agencies including police will begin checks and the analysis of information from partner agencies

- Discussion will take place on threshold decision and a strategy meeting convened where a multiagency agreement will be reached whether the matter will be dealt with as a joint or single enquire with police.

- All suspicions of physical abuse will follow this policy and an on-call safeguarding paediatrician will be invited to attend the strategy meeting to decide whether a CP medical is required.

- Where a medical is required, this will then be organised between chairing mash manager and paediatrician. The social worker will accompany child and parents to the CP medical.

- The social worker must ensure that the adult who attends with the child has parental responsibility and can give consent to the medical.

The assessment of the child should be carried out by a paediatrician with Level 3 competencies as per Safeguarding Children and Young People: Roles and Responsibilities for Healthcare Staff. Where a trainee carries out the assessment, they should be supervised by a consultant or senior paediatrician and should be at least ST4 level RCPCH 2020. The on-call Consultant Paediatrician should ensure that they or a nominated middle grade or specialist doctor, as a minimum. The paediatrician is required to:

- Take and record full details of the case

- Be part of the initial strategy discussion and decide together, with the Social worker, the arrangements for and management of the medical examination and whether further action is required

- Record the decision in the child’s notes

- Medical assessments should be recorded on the Child Protection Medical Proforma in accordance with policy in the majority of cases. If the child is admitted through the Emergency Department the paediatric admission booklet may be used with use of body maps to document injuries accurately. Good practice guidelines should be followed as per the Child Protection Companion

- The Consultant Paediatrician holds ultimate responsibility for the case, regardless of whether a middle grade health practitioner performs some of the above actions

- A written provisional medical opinion should be given to the attending social worker immediately following the medical assessment, giving a clear summary of the findings and level of concern in respect of the abuse. A full typed report should follow.

- The child’s GP and health visitor should be informed of the child protection medical assessment report findings within 48 hours, which may be by copy of the provisional medical opinion.

Chapter 9 Recognition of Physical Abuse. Child Protection Companion. RCPCH online document accessed June 2019 (RCPCH Child Protection Portal – Child protection and safeguarding in the UK: your essential resource to help inform clinical practice, child protection procedures, and professional and expert opinion in the legal system)

Bruises on Children: Core Info leaflet. Updated September 2018

https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/pre-2013/bruises-children-core-info-leaflet

https://childprotection.rcpch.ac.uk/child-protection-evidence/bruising-systematic-review/