Please select a partnership to see additional information:

1.18 Additional guidance

Contents

- Assessments under The Children Act 1989(Jump to)

- Definitions of abuse and neglect(Jump to)

- Inter-authority arrangements for child protection enquiries(Jump to)

- Involving the child, their parents and family(Jump to)

- Looked after children and child protection conferences(Jump to)

- Medical evidence(Jump to)

- Pre-birth procedures(Jump to)

- Review conferences(Jump to)

- The assessment framework(Jump to)

- The concept of significant harm(Jump to)

- Transfer-in conferences(Jump to)

- Visually recorded interviews(Jump to)

- Complaints by children and/or parents(Jump to)

- Children on child protection plans who go missing(Jump to)

- Adult with care and support needs(Jump to)

- West Midlands Joint Protocol - Child Protection Enquiries and Related Criminal Investigations(Jump to)

- West Midlands Protocol - Protecting Children who Move Across Local Authority Borders(Jump to)

- Local Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews: Statutory guidance, regional framework and practice guidance(Jump to)

- Children living or being taken abroad(Jump to)

- After-school clubs(Jump to)

Local authority children’s social care assess the needs of individual children to determine which services to provide and what action to take. The full set of statutory assessments available under the Children Act 1989 are described on this page.

Where a child in need has moved permanently to another local authority area, the original authority should ensure that all relevant information (including the child in need plan) is shared with the receiving local authority as soon as possible. The receiving local authority should consider whether support services are still required and discuss with the child and family what might be needed, based on a timely re-assessment of the child’s needs, as set out in this chapter. Support should continue to be provided by the original local authority in the intervening period. The receiving authority should work with the original authority to ensure that any changes to the services and support provided are managed carefully.

Where a child in need is approaching 18 years of age, this transition point should be planned for in advance. This includes where children are likely to transition between child and adult services.

Section 17 assessment of a ‘child in need’

A ‘child in need’ is defined under the Children Act 1989 as a child who is unlikely to achieve or maintain a reasonable level of health or development, or whose health and development is likely to be significantly or further impaired, without the provision of services; or a child who is disabled.

Children in need may be assessed by a social worker under section 17 of the Children Act 1989 in relation to their special educational needs, disabilities, as a carer, or because they have committed a crime. This process for assessment should also be used for children whose parents are in prison and for asylum seeking children. When assessing children in need and providing services, specialist assessments may be required and, where possible, should be coordinated so that the child and family experience a coherent process and a single plan of action.

When undertaking an assessment of a disabled child, the local authority must also consider whether it is necessary to provide support under section 2 of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act (CSDPA) 1970. Where a local authority is satisfied that the identified services and assistance can be provided under section 2 of the CSDPA, and it is necessary in order to meet a disabled child’s needs, it must arrange to provide that support.

Section 47 enquiry for children suffering, or likely to suffer, significant harm

Where a child is suspected to be suffering, or likely to suffer, significant harm, the local authority is required by section 47 of the Children Act 1989 to make enquiries to enable it to decide whether it should take action to safeguard and promote the welfare of the child. More information on section 47 enquiries can be found in these procedures.

It should be noted that there may be a need for immediate protection whilst the assessment is carried out.

Accommodation under section 20

Some children in need may require accommodation because there is no one who has parental responsibility for them, because they are lost or abandoned or because the person who has been caring for them is prevented from providing them with suitable accommodation or care. Under section 20 of the Children Act 1989, the local authority has a duty to accommodate such children in need in their area.

Assessment of children on care orders

Where a child is the subject of a care order following an application under section 31A, the local authority, as a corporate parent, must assess the child’s needs and draw up a care plan which sets out the services which will be provided to meet the child’s identified needs.

Assessment of young carers

If a local authority considers that a young carer may have support needs, they must carry out an assessment under section 17ZA. The local authority must also carry out an assessment if a young carer, or the parent of a young carer, requests one. The assessment must consider whether it is appropriate or excessive for the young carer to provide care for the person in question, in light of the young carer’s needs and wishes.

The Young Carers’ (Needs Assessment) Regulations 2015 require local authorities to look at the needs of the whole family when carrying out a young carers’ needs assessment. Young carer’s assessments can be combined with assessments of adults in the household with the agreement of the young carer and adults concerned.

Assessment of parents/carers of disabled children

When undertaking an assessment of a disabled child, the local authority must also consider whether it is necessary to provide support under section 2 of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act (CSDPA) 1970. Where the local authority is satisfied that the identified services and assistance can be provided under section 2 of the CSDPA, and it is necessary in order to meet a disabled child’s needs, it must arrange to provide that support. Where the local authority is assessing the needs of a disabled child, a carer of that child may also require the local authority to undertake an assessment of their ability to provide, or to continue to provide, care for the child, under section 1 of the Carers (Recognition and Services) Act 1995. The local authority must take account of the results of any such assessment when deciding whether to provide services to the disabled child.

If a local authority considers that a parent or carer of a disabled child may have support needs, they must carry out an assessment under section 17ZD. The local authority must also carry out such an assessment if a parent or carer requests one. The assessment must consider whether it is appropriate for the parent or carer to provide, or continue to provide, care for the disabled child, in light of the parent or carer’s needs and wishes.

Assessment of children in secure youth establishments

Any assessment of children in secure youth establishments should take account of their specific needs. In all cases, the local authority in which a secure youth establishment is located is responsible for the safety and welfare of the children in that establishment. The local authority should work with the governor, director, manager or principal of the secure youth establishment and the child’s home local authority, their relevant Youth Offending Team and, where appropriate, the Youth Custody Service to ensure that the child has a single, comprehensive support plan.

Where a child becomes looked-after, as a result of being remanded to youth detention accommodation (YDA), the local authority must visit the child and assess the child’s needs before taking a decision. This information must be used to prepare a Detention Placement Plan (DPP), which must set out how the YDA and other practitioners will meet the child’s needs whilst the child remains remanded. The DPP must be reviewed in the same way as a care plan for any other looked-after child.

Assessment of risk outside the home (contextual safeguarding)

As well as threats to the welfare of children from within their families, children may be vulnerable to abuse or exploitation from outside their families. These extra-familial threats might arise at school and other educational establishments, from within peer groups, or more widely from within the wider community and/or online. These threats can take a variety of different forms and children can be vulnerable to multiple threats, including: exploitation by criminal gangs and organised crime groups such as county lines; trafficking, online abuse; teenage relationship abuse; sexual exploitation and the influences of extremism leading to radicalisation. Extremist groups make use of the internet to radicalise and recruit and to promote extremist materials. Any potential harmful effects to individuals identified as vulnerable to extremist ideologies or being drawn into terrorism should also be considered. Further information on the signs of a child’s involvement in county lines is available in The Children’s Society County Lines Toolkit For Professionals.

Assessments of children in such cases should consider whether wider environmental factors are present in a child’s life and are a threat to their safety and/or welfare. Children who may be alleged perpetrators should also be assessed to understand the impact of contextual issues on their safety and welfare. Interventions should focus on addressing these wider environmental factors, which are likely to be a threat to the safety and welfare of a number of different children who may or may not be known to local authority children’s social care. Assessments of children in such cases should consider the individual needs and vulnerabilities of each child. They should look at the parental capacity to support the child, including helping the parents and carers to understand any risks and support them to keep children safe and assess potential risk to child.

Channel panels, established under the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, assess the extent to which identified individuals are vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism, and, where appropriate, arrange for support to be provided. When assessing Channel referrals, local authorities and their partners should consider how best to align these with assessments undertaken under the Children Act 1989.

The Children Act 1989 promotes the view that all children and their parents should be considered as individuals and that family structures, culture, religion, ethnic origins and other characteristics should be respected. Local authorities should ensure they support and promote fundamental British values, of democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs.

The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 contains a duty on specified authorities in England, Wales and Scotland to have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism.

Child abuse occurs throughout society and affects children of all ages. Somebody may abuse or neglect a child by inflicting harm, or by failing to act to prevent harm.

Physical abuse

Physical abuse may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating, or otherwise causing physical harm to a child.

Physical harm may also be caused when a parent feigns the symptoms of, or deliberately causes, illness in a child. This is known as fabricated or induced illness.

Emotional abuse

Emotional abuse is the persistent emotional maltreatment of a child such as to cause severe and persistent effects on the child's emotional development, and may involve:

- conveying to children that they are worthless or unloved, inadequate, or valued only insofar as they meet the needs of another person

- imposing age or developmentally inappropriate expectations on children. These may include interactions that are beyond the child's developmental capability, as well as overprotection and limitation of exploration and learning, or preventing the child participating in normal social interaction

- seeing, hearing or experiencing the ill-treatment of another e.g. where there is domestic violence and abuse

- serious bullying (including cyber bullying), causing children frequently to feel frightened or in danger;

- exploiting and corrupting children.

Some level of emotional abuse is involved in all types of maltreatment of a child, though it may occur alone.

Sexual abuse

Sexual abuse involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (e.g. rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing.

Sexual abuse includes non-contact activities, such as: involving children in looking at or producing pornographic materials, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse (including via the internet). Sexual abuse can take place online, and technology can be used to facilitate offline abuse. Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children.

Sexual abuse also includes abuse of children through sexual exploitation. Penetrative sex where one of the partners is under the age of 16 is illegal, although prosecution of similar age, consenting partners is not usual. However, where a child is under the age of 13 it is classified as rape.

Neglect

Neglect is the persistent failure to meet a child's basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child's health or development.

Neglect may occur during pregnancy as a result of maternal substance misuse, maternal mental ill health or learning difficulties or a cluster of such issues.

Once a child is born, neglect may involve a parent failing to:

- provide adequate food, clothing and shelter (including exclusion from home or abandonment)

- protect a child from physical and emotional harm or danger

- ensure adequate supervision (including the use of inadequate care-givers)

- ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment.

It may also include neglect of, or unresponsiveness to, a child's basic emotional, social and educational needs.

These definitions are used when determining significant harm. Children can be affected by combinations of abuse and neglect, which may also be related to problems faced by the adults in the household such as domestic violence and abuse.

Domestic violence

Research analysing Serious Case Reviews has demonstrated a significant prevalence of domestic abuse in the history of families with children who are subject of Child Protection Plans. Children can be affected by seeing, hearing and living with domestic violence and abuse as well as being caught up in any incidents directly, whether to protect someone or as a target.

It should also be noted that the age group of 16 and 17 year olds have been found in recent studies to be increasingly affected by domestic violence in their peer relationships.

The Home Office definition of Domestic violence and abuse was updated in March 2013 as:

"Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence and abuse between those aged 16 or over, who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender and sexuality.

This can encompass, but is not limited to, the following types of abuse:

- psychological

- physical

- sexual

- financial

- emotional

Controlling behaviour is: a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.

Coercive behaviour is: an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.

Further information about recognising the signs of abuse and neglect has been published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Responsibility for section 47 enquiries rests with the local authority children’s social care for the area where the child is living or is found. For these purposes, 'found' means the physical location where the child suffers, or is identified to be at risk of, harm or neglect.

Usually the area where the child is living is the same as the physical location where the child suffers, or is identified to be at risk, of harm and neglect. However, these may be different. For example:

- a child found in one authority but subject to a child protection plan in another authority

- a looked after child placed in another local authority

- a child attending a boarding school in another area

- a child receiving in-patient treatment in another area

- a family currently receiving services from another local authority

- a child staying temporarily in the area but whose family continues to live in another authority

- a family who have moved into the area, but where another authority retains case responsibility temporarily

- a child suspected of being abused by a paedophile operating in another local authority are to the area the child lives.

Where more than one authority is involved, immediate and full consultation should take place between both areas to agree how enquiries will be planned and undertaken. However, negotiations about responsibility must not cause delay in urgent situations.

Any emergency action should be taken by the area where the child is suffering, or at risk of suffering, harm or neglect (unless agreement is reached the authority where the child normally lives will assume this responsibility).

The area where the child lives will be responsible if concerns relate to the child’s home circumstances or if the concerns are in relation to the child’s parenting.

Where the concerns arise in relation to the child’s circumstances where they do not normally live (for example, abuse in a school or placement) the authority where the neglect, harm or abuse takes places should lead the enquiry, liaising closely with the authority where the child lives.

The authority where the child lives will be responsible for the provision of any form of foster or residential care or other services to ensure the protection of a child found in another authority.

It is important that the principles of partnership with the child, their parents and family are maintained throughout the child protection process.

Listening to and involving the child

- The interests of the child must always remain at the centre of the child protection process.

- The child should be listened to whenever they report they are suffering, or have suffered, significant harm through abuse and neglect.

- The child should be supported to participate directly in all child protection processes based on their age and understanding (see criteria for involvement below).

- Additional measures may be required for a child with communication difficulties (for example, in consequence of a disability).

- It should always be explained to the child that, whilst their view will be taken into account, the professional has a responsibility to take whatever action is required to ensure their safety and the safety of other children.

Involving parents/carers

- Concerns should be discussed with the parent and agreement sought for a referral to local authority children's social care unless seeking agreement is likely to place the child at risk of significant harm through delay, or the parent's actions or reactions, or lead to the risk of loss of evidential material.

- Parents/carers should always be involved throughout the child protection processes unless to do so would prejudice the safety of the child.

- The lead social worker should ensure that parents and carers understand how they can contribute to the process and what is expected of them to change in order to improve the outcomes for the child.

- The best interests of the child must always remain paramount but reasons for proceeding without parental agreement must be recorded and shared with the parent/carer.

Involving the child

The interests of the child must always remain at the centre of the child protection process. The child should either be supported to participate directly, where appropriate based on their age and understanding, or indirect methods used to ensure the child’s views are considered at all stages in the process.

Criteria for involvement

The following questions should be considered when determining how a child should be involved:

- Does the child have sufficient understanding of the process?

- Have they expressed an explicit or implicit wish to be involved?

- What are the parents’ views about the child’s proposed presence at Child Protection Conferences or Core Group meetings?

- Is inclusion assessed to be of benefit to the child?

The test of 'sufficient understanding' is partly a function of age and partly the child's capacity to understand. The following approach is recommended:

- A presumption (that can be rebutted by evidence to the contrary) that a child of less than twelve years of age is unlikely to be able to be a direct and/or full participant in a forum such as a child protection conference;

- A presumption (also rebuttable by evidence to the contrary) that from the age of twelve and over, a child should be offered such an opportunity.

Attendance at Child Protection Conferences or Core Group meetings

The appropriateness of including an individual child at a Child Protection Conference or Core Group meeting must be assessed in advance and relevant arrangements made to facilitate attendance at all or part of the conference or meeting.

A child’s declared wish not to attend a conference or meeting must be respected.

Consideration should also be given to:

- the impact of the conference on the child (for example, where it will be impossible to ensure they are kept apart from a parent who may be hostile and/or attribute responsibility to them).

- the extent to which it is appropriate for a child to hear details of a parent's personal difficulties (a parent's view about this should be respected).

Direct involvement of a child in a conference

In advance of the conference, the independent chair and social worker should agree whether:

- the child attends for all or part of the conference, taking into account confidentiality or parents and/or siblings

- the child should be present with one or more of their parents

- the chair meets the child alone or with a parent prior to the meeting.

It may be appropriate to arrange for the child to be accompanied by a supporter or advocate.

If a child attends all or part of the conference, it is essential that they are prepared by the social worker or independent advocate who can help them prepare a report or rehearse any particular points that the child wishes to make.

Provision should be made to ensure that a child who has any form of disability is enabled to participate.

Indirect contributions when a child is not attending

Where it would be inappropriate for the child to attend a conference or meeting, alternative arrangements should be made to ensure their wishes and feelings are made clear to all relevant parties.

Indirect contributions from a child should, whenever possible, include a pre-meeting with the independent conference chair.

Other indirect methods include written statements, e-mails, text messages and taped comments prepared alone or with independent support, and representation via an advocate.

Professionals should be able to represent a child's views and a particular responsibility falls upon the social worker to do so. It is important that the child feels involved in the whole process of child protection rather than merely receiving an invitation to the conference or meeting.

Involving parents and other family members

The child’s parents (including a parent who does not live with the child or any other individual who has parental responsibility) must be invited and encouraged to participate in all child protection meetings unless to do so would prejudice the welfare of the child.

Family members (including the wider family) who have been identified during the assessment as able to provide support to the child or parents, or as potential suitable alternative carers if the child cannot continue to live with the parents, should also be invited to child protection conferences and subsequent Core Group meetings as appropriate.

They should be invited to meet with the independent chair prior to any child protection conference to ensure they understand the purpose of the conference and the processes that will be used.

It may also be appropriate to facilitate access to advocates to support parents.

Those parents and family members for whom English is not a first language must be offered and provided with an interpreter, if required. A family member should not be expected to act as an interpreter of spoken or signed language.

Exclusion of family members from a Child Protection Conference

Exceptionally, it may be necessary to exclude one or more family members from a conference, in whole or in part.

There are a number of possible reasons why an exclusion may be necessary, including:

- indications that the presence of the parent or family member may prejudice the welfare of the child

- evidence that a parent or family member may behave in manner that will interfere with the work of the conference such as violence, threats of violence, racist or other forms of discriminatory or oppressive behaviour, or being in an unfit state (for example, through drug, alcohol consumption or acute mental health difficulty)

- a child requests that the parent/person with parental responsibility is not present while they are present

- the presence of the individual concerned would prevent a professional from making their proper contribution through concerns about violence or intimidation

- a parent or family member does not wish another parent or family member to be there due to concerns about intimidation, e.g. where domestic violence has occurred

- the need for members to receive confidential information that would otherwise be unavailable, such as legal advice or information about a criminal investigation

- conflicts between different family members who may not be able to attend at the same time.

If a professional believes that a parent or family member should be excluded from a conference, they should contact the independent Chair as soon as possible (ideally at least three working days in advance of the proposed meeting) and give reasons and evidence why they believe the individual should be excluded.

The independent Chair must consider the representation carefully and may need legal advice. Any exclusion should be for the minimum duration necessary and must be clearly recorded in the conference record. Exclusion at one conference is not reason enough in itself for exclusion at further conferences.

If the independent Chair decides to exclude a parent, this must be communicated in writing with information on how they may make their views known, how they will be told the outcome of the conference and about the complaints procedure.

The independent Chair will determine whether or not the excluded parent should receive the record of the conference. Where a parent attends only part of a conference as a result of exclusion, they must receive the record of the conference. The Chair should decide if the entire record is provided or only that part attended by the excluded parent.

It may also become clear in the course of a conference that its effectiveness will be seriously impaired by the presence of the parent/s or family members. In these circumstances the independent Chair may ask them to leave.

Where a parent is on bail, or subject to an active police investigation, it is the responsibility of the independent Chair to ensure that the police representative can fully present their information and views and also that the parents participate as fully as circumstances allow.

The decision of the independent Chair over matters of exclusion is final regarding both parents and the child.

The absence of parents and children

If parents and/or child do not wish to attend a Child Protection Conference or Core Group meeting they must be provided with full opportunities to contribute their views. The social worker must facilitate this by:

- the use of an advocate or supporter to attend on behalf of the parent or child

- enabling the child or parent to write or tape or use drawings to represent their views

- agreeing that the social worker, or any other professional, expresses their views.

Complaints by children and/or parents

Parents and, on occasion, children may wish to make representations or complain in respect of one or more of the following aspects of the functioning of child protection conferences:

- the process of the conference

- the outcome, in terms of the fact of and/or the category of primary concern at the time the child became the subject of a child protection plan

- a decision for the child to become, to continue or not to become, the subject of a child protection plan.

See additional guidance, Complaints by Children and/or Parents, for details of the process for dealing with complaints.

When a child with a child protection plan becomes ‘looked after’ by the local authority, in most cases it will no longer be necessary to maintain the child protection plan. Similarly, children who are already looked after will not usually be the subject of child protection conferences.

Children with child protection plans who become looked after under section 20 of the Children Act 1989

If a child with a child protection plan becomes looked after under section 20, their legal situation is not permanently secure and the next Review conference should consider the child’s safety in the light of the possibility that the parent can simply request their removal from the local authority's care. The Review conference must be sure that the looked after child Care Plan provides adequate security for the child and sufficiently reduces or eliminates the risk of significant harm identified by the initial child protection conference.

If a child ceases to be subject of a child protection plan as a result of a decision at a Review conference, and the parent then unexpectedly requests the return of the child from the local authority's care, children’s social care should consider the need for an initial child protection conference.

Review conferences for looked after children

In the limited number of cases where a child protection plan is still required, it should form part of the child’s wider Care Plan and the timing of the review of the child protection aspects of the Care Plan should align with those of the statutory Care Plan review. This could be achieved by holding the child protection Review conference at the same place immediately before a Care Plan review. This will ensure that up to date information in relation to the child's welfare and safety is considered within the review meeting and informs the overall care planning process.

Consideration should also be given to the Independent Reviewing Officer (IRO) chairing the child protection conference where a looked after child remains the subject of a child protection plan despite there being:

- different requirements for independence of the IRO function compared to the chair of the child protection conference,; and

- a requirement for the child protection conference to be a multi-agency forum.

This should be decided on an individual case basis and managed to ensure that the independence of the IRO is not compromised. Where it is not possible for the IRO to chair the child protection conference, the IRO should attend.

Where the child requires medical attention (for example, suspected fractures, bleeding, loss of consciousness), they should be taken to the nearest emergency department.

In other circumstances where a medical assessment may be required, the strategy meeting/discussion will determine, in consultation with the paediatrician, the need and timing for the assessment.

Where a child is also to be interviewed by police and/or local authority children's social care, this interview should take place prior to a medical examination unless there are exceptional circumstances.

The purpose of a medical assessment

The purpose of a medical assessment is to ascertain whether there is any medical evidence to support the existence or extent of abuse or other serious health needs and, if necessary, to treat the child.

A medical assessment will be necessary when any of the following apply:

- There is a reasonable suspicion of significant harm to a younger or otherwise vulnerable child (usually below the age of ten or having a disability which impairs the ability to communicate about any abuse being suffered).

- There is a serious injury and assault is established or considered likely.

- There are inconsistencies in the explanations given which require expert examination

- There have been previous injuries.

- There are indications of detectable previous injuries, or neglect, or other suspicious physical presentations.

- There is an allegation of sexual abuse.

The need for the assessment in the context of the section 47 enquiries should be discussed with the doctor due to undertake the medical assessment to ensure they are aware of its strategic significance. The person taking the child for the assessment should also be fully aware of the child’s circumstances and the purposes of the assessment.

Consent

Consent is required for a medical assessment. This may be may be given by:

- Any person with parental responsibility, providing they have the capacity to do so.

- A child of sufficient age and understanding. However, wherever possible, the permission of a parent should be sought for children under 16.

- A young person aged 16 or 17. This is an explicit right under section 8 of the Family Law Reform Act 1968 and, unless grounds exist for doubting their mental capacity, no further consent is required for 16 and 17 year olds.

- The local authority when the child is the subject of a care order (although the parent should be informed).

- The child’s current carer if the parents cannot be contacted or are assessed as lacking capacity to give such authority. This includes the local authority when the child is accommodated under section 20 of the Children Act 1989.

- The High Court when the child is a ward of court.

- A family proceedings court as part of a direction attached to an emergency protection order, an interim care order or a child assessment order.

A child who is of sufficient age and understanding may refuse some or all of a medical assessment. Refusal should only be overridden by a court. The child’s attention should be drawn to their right to give or refuse consent to an examination or treatment if they are 16 or over, or if the child is under 16 and the doctor considers they have sufficient understanding to understand the consequences of consent or refusal.

Legal advice should be sought if it is not clear who can provide consent for a particular child. If the appropriate consent cannot be obtained it is inadvisable to conduct a formal child protection medical assessment. In this situation a carefully recorded clinical examination and necessary treatment may still be undertaken, with the consent of the child where appropriate. In these circumstances, parents must be informed by the medical practitioner as soon as possible and a full record must be made at the time.

In non-emergency situations, when parental permission is not obtained, the local authority children’s social care must consider whether it is in the child's best interests to seek a court order.

Conducting a medical assessment

Only doctors may physically examine the child. This will normally be a paediatrician. GPs must not perform a detailed examination in cases of suspected abuse unless this is agreed by the police and local authority children's social care. All other staff should only note any visible marks or injuries on a body map and then date and sign the record in the child's file.

Wherever possible, a child should have the choice of a male or female doctor and only one diagnostic medical assessment should take place. However, a paediatrician may refer on to other professionals, particularly if there are suspicions of sexual abuse.

A medical assessment should demonstrate a holistic approach to the child and assess the child's well-being, including mental health, development and cognitive ability.

The examining doctor should provide a report to the social worker, the GP and where appropriate, the police. The timing of a letter to parents should be determined in consultation with local authority children's social care and the police.

The report should include:

- a verbatim record of the carer's and child's accounts of injuries and concerns noting any discrepancies or changes of story

- documentary findings in both words and diagrams

- site, size, shape and where possible age of any marks or injuries

- opinion of whether injury is consistent with explanation

- date, time and place of examination

- those present

- who gave consent and how (child/parent, written/verbal)

- other findings relevant to the child (for example, squint, learning or speech problems etc)

- confirmation of the child's developmental progress (especially important in cases of neglect)

- the time the examination ended.

All reports and diagrams should be signed and dated by the doctor undertaking the examination.

Referral

Where agencies or individuals anticipate that prospective parents may need support services to care for their baby or that the unborn child may have suffered, or be likely to suffer, significant harm, a referral to local authority children's social care must be made as soon as concerns are identified.

A referral should be made at the earliest opportunity in order to:

- provide sufficient time to make adequate plans for the baby's protection

- provide sufficient time for a full and informed assessment

- avoid initial approaches to parents in the last stages of pregnancy, at what is already an emotionally charged time

- enable parents to have more time to contribute their own ideas and solutions to concerns and increase the likelihood of a positive outcome for the baby

- enable the early provision of support services so as to facilitate optimum home circumstances prior to the birth.

Early referral is also essential if legal action is required to protect the unborn child. Statutory guidance advises local authorities to take into account the risk of early birth and to send pre-proceedings letters/letters of issue before 24 weeks.

The referrer should clarify as far as possible, using the local early help assessment arrangements or the equivalent, their concerns in terms of how the parent's circumstances and/or behaviours may impact on the baby and what risks are predicted.

Concerns should be shared with prospective parent/s and consent obtained to refer to local authority children's social care unless obtaining consent in itself may place the welfare of the unborn child at risk e.g. if there are concerns that the parent/s may move to avoid contact with investigative agencies.

Pre-birth assessment

A pre-birth assessment should be undertaken on all pre-birth referrals as early as possible, preferably before 20 weeks, where:

- a parent or other adult in the household, or regular visitor, has been identified as posing a risk to children

- a sibling in the household is subject of a child protection plan

- a sibling has previously been removed from the household either temporarily or by court order

- the parent is a looked after child

- there are significant domestic violence issues

- the degree of parental substance misuse is likely to impact significantly on the baby's safety or development

- there are significant concerns about parental ability to self-care and/or to care for the child e.g. unsupported, young or learning disabled mother

- any other concern exists that the baby may have suffered, or is likely to suffer, significant harm including a parent previously suspected of fabricating or inducing illness in a child or harming a child

- a child aged under 13 is found to be pregnant.

Pre-birth Strategy Meeting/Discussion and Section 47 enquires

The need for a section 47 enquiry should be considered and, if appropriate, initiated at a strategy meeting/discussion held as soon as possible following receipt of the referral. The expected date of delivery will determine the urgency of the meeting

Consideration of the need to initiate a section 47 enquiry and hold a strategy meeting/discussion should follow the procedures described in chapters 8 and 9 of these procedures (Strategy Meeting/Discussion and Child Protection Enquiries). Ideally the strategy meeting/discussion should take place at the hospital where the birth is planned or expected, or where the responsible midwifery service is where it would be if the parents have not booked for service provision.

The meeting must decide:

- Whether a section 47 enquiry and pre-birth assessment is required (unless previously agreed at any earlier ante-natal meeting).

- What areas are to be considered for assessment.

- Who needs to be involved in the process.

- How and when the parent/s are to be informed of the concerns.

- The actions required by adult services working with expectant parent/s (male or female).

- The actions required by the obstetric team as soon as the baby is born. This includes labour/delivery suite and post-natal ward staff and the midwifery service, including community midwives.

- Any instructions in relation to invoking an emergency protection order (EPO) at delivery should be communicated to the midwifery manager for the labour/delivery suite.

The parents should be informed as soon as possible of the concerns and the need for assessment, except on the rare occasions when medical advice suggests this may be harmful to the health of the unborn baby and/or mother.

The section 47 enquiry must make recommendations regarding the need, or not, for a pre-birth child protection conference.

Pre-birth Child Protection Conferences

A pre-birth conference is an initial child protection conference concerning an unborn child. Pre-birth conferences should always be convened where there is a need to consider if a multi-agency child protection plan is required. This decision will usually follow from a section 47 enquiry and pre-birth assessment.

A pre-birth conference should be held where:

- a pre-birth assessment gives rise to concerns that an unborn child may have suffered, or is likely to suffer, significant harm

- a previous child has died or been removed from parent/s as a result of significant harm

- a child is to be born into a family or household that already has children who are subject of a child protection plan

- an adult or child who is a risk to children resides in the household or is known to be a regular visitor.

Other risk factors to be considered include:

- the impact of parental risk factors such as mental ill health, learning disabilities, substance misuse and domestic violence

- a mother under 18 years of age about whom there are concerns regarding her ability to self-care and/or to care for the child.

A pre-birth conference has the same status as an initial child protection conference and must be conducted in a comparable manner (see Child Protection Conferences).

The conference should be held as soon as the assessment has been completed and at least 10 weeks before the due date of delivery. Where there is a known likelihood of a premature birth, the conference should be held earlier.

Review conferences consider whether the child protection plan should continue or should be changed. They review whether the child is continuing to suffer, or is likely to suffer, significant harm, and review developmental progress against the child protection plan outcomes.

Thorough regular review is critical to achieving the best possible outcomes for the child and includes:

- sharing and analysing up-to-date information about the child's health, development and functioning and the parent's capacity to ensure and promote the child's welfare

- maintaining contact with health professionals such as GPs, Health Visitors, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and adult mental health service professionals

- considering the impact on the child of the capacity and functioning of the parent/carer

- ensuring that the measures already in place to safeguard the child from harm are effective and in line with local arrangements

- regularly reviewing the progress of all aspects of the child protection plan

- making changes to the child protection plan (for example, where a family is not co-operating)

- deciding what action is required to safeguard the child if there are changes to the child's circumstances

- setting or re-setting desired outcomes and timescales

- seeking and taking into account the child's (possibly changed) wishes and feelings

- making judgements about the likelihood of the child suffering significant harm in the future

- deciding whether there is a need for a new assessment.

Holding a review conference

The review conference procedures for preparation, decision-making, membership and recording should be the same as for all child protection conferences.

The first child protection Review conference should be held within three months of the date of the initial child protection conference.

Further reviews should be held at intervals of not more than six months for as long as the child remains the subject of a child protection plan. If the initial conference was a pre-birth conference the Review conference should take place within one month of the child's birth or within three months of the date of the pre-birth conference, whichever is sooner.

All Review conferences should consider the timescales to meet the needs and safety of the child. An infant or child under the age of 5 where there are serious concerns about the levels of risk might require the timescales to be shorter than those set above.

Reviews should be brought forward where/when:

- child protection concerns relating to a new incident or allegation of abuse have been sustained

- there are significant difficulties in carrying out the child protection plan

- a child is to be born into the household of a child or children already subject of child protection plans

- an adult or child who poses a risk to children is to join, or commences regular contact with, the household

- there is a significant change in the circumstances of the child or family not anticipated at the previous conference and with implications for the safety of the child

- a child subject of a child protection plan is also looked after by the local authority and consideration is being given to returning them to the circumstances where care of the child previously aroused concerns (unless this step is anticipated in the existing child protection plan)

- the core group believe that an early cancellation of the need for a child protection plan should be considered.

Outcome of a review conference

Every review conference will update the child protection plan:

- If the key issues have been resolved, the conference should conclude that a child protection plan is no longer needed and it should therefore be converted to a child in need plan. For further information see the section on discontinuing a child protection plan.

- It there has been satisfactory progress toward achieving the outcomes in the child protection plan but key issues have not yet been adequately addressed, the conference may consider that the child protection plan should continue in force and arrange a further conference.

- If the family have not made satisfactory progress toward achieving the outcomes and/or addressing the key issues by the second review, the conference should recommend that children’s social care take legal advice about initiating family proceedings.

- If the risk to the child appears to be increasing the conference may recommend that children’s social care take urgent action to remove the child.

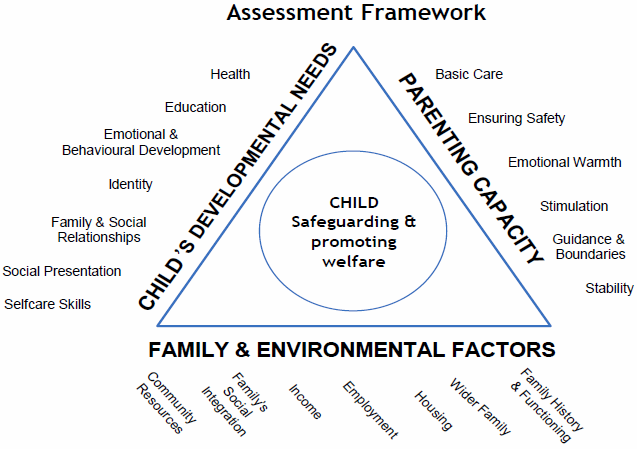

The assessment stage involves gathering and analysing information under the three domains of the assessment framework. These are the:

- child’s developmental needs

- parents’ or caregivers’ capacity to respond appropriately

- impact of the wider family and environmental factors on parenting capacity and children.

The aim is to reach a judgement about the nature and level of needs and/or risks that the child may be facing within their family. It is important that:

- information is gathered and recorded systematically

- information is checked and discussed with the child and their parents/carers where appropriate

- differences in views about information are recorded, and

- the impact of what is happening to the child is clearly identified.

The Children Act 1989 introduced the concept of significant harm as the threshold which justifies compulsory intervention in family life in the best interests of children. Section 47 of the Act places a duty on local authorities to make enquiries, or cause enquiries to be made, where it has reasonable cause to suspect that a child is suffering, or is likely to suffer significant harm.

There are no absolute criteria for establishing significant harm. Whether the harm, or likely harm, suffered by the child is significant is determined by comparing the child’s health or development with that which could reasonably be expected of a similar child.

‘Harm’ can include the effect of seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of someone else, for example where there are concerns of domestic violence and abuse.

Sometimes, a single traumatic event may constitute significant harm (e.g. a violent assault, suffocation or poisoning). More often, significant harm is a compilation of significant events which interrupt, change or damage the child's physical and psychological development.

When considering the severity of ill-treatment, it can be useful to consider:

- the degree and the extent of physical harm

- the duration and frequency of abuse and neglect

- the extent of premeditation, and

- the presence or degree of threat, coercion, sadism and bizarre or unusual elements.

Some children live in family and social circumstances where their health and development are neglected. For them, it is the corrosiveness of long-term neglect, emotional, physical or sexual abuse that causes impairment to the extent that it constitutes significant harm.

To understand and establish ‘significant harm’, professionals should consider a range of factors including:

- the family context, including protective factors

- the child’s development within the context of his or her family and wider social and cultural environment

- any special needs, such as a medical condition, communication difficulty or disability that may affect the child’s development and care within the family

- the nature of harm, in terms of ill-treatment or failure to provide adequate care

- the impact on the child’s health and development

- the capacity of the parent or carer to adequately meet the child’s needs.

Transfer-in conferences should take place when a child who is the subject of a child protection plan moves, or plans to move, permanently from one local authority area to another. (A permanently move is usually defined as a period of more than 3 months.)

A Transfer-in conference has the same status and purpose and must be conducted in a comparable manner to an initial child protection conference.

Organising the Transfer-in Conference

Timing

The local authority children’s social care for the area the child has moved to should convene the Transfer-in conference within 15 working days from the date the child moved permanently into the area (or 15 working days from when they were notified).

Information

The Transfer-in conference must have access to all the information available to make fully informed decisions and develop a robust child protection plan. To facilitate this the Transfer-in conference should receive comprehensive reports from professionals in the area the child has left.

Professionals in agencies in the area the child has moved to (or is planning to move to) must ensure that the conference has all relevant information from their counterparts in the area the child has left – this may require them to make a request for further information. They should also provide any new information to the conference.

Before going ahead, the local authority children’s social care for the area the child has moved to should also ensure that the conference has received sufficient information to:

- understand the details of the case

- understand the child protection plan and safeguarding arrangements.

If necessary, they should seek clarification from agencies in the area the child has left.

Attendance

The conference should be held in the area the child has moved to. Professionals from the area the child has left who are significant in the existing child protection plan must be invited to the conference. Wherever practical these professionals should attend the conference.

Interim arrangements

The responsibility for the child and for the implementation of their child protection plan remains with the local authority where the family previously lived until:

- the Transfer-in conference has taken place, and

- the area the child has moved to makes a formal decision about the continuing need for a child protection plan, and

- the decision is confirmed in writing.

During the period before the Transfer-In conference, the local authority for the area the child has moved to should place the child on its database of children subject to a child protection plans from the date of the actual move (or when informed of the move if this is later).

If a family moves to an area that is too far away for the existing Social Worker to effectively carry out home visits and other tasks required by the child protection plan, the local authority in the area the child has moved to should assist by implementing the plan prior to the formal Transfer-in conference. The agreement to do this must be confirmed in writing within one week of the family moving.

Outcome of a Transfer-in Conference

A Transfer-in Conference will:

- make a decision about the continuing need for a child protection plan

- arrange for responsibility to be transferred to the authority the child has moved to (if a decision is made to continue with the child protection plan).

The Transfer-in conference may transfer responsibility but recommend joint work with professionals from agencies in the area the child has left continues for a time limited period. Where this occurs, professionals must comply with the terms of the revised child protection plan.

The decisions made at a Transfer-in conference should be confirmed in writing.

Visually recorded interviews serve two primary purposes:

- Evidence gathering in a criminal investigation.

- Evidence to be presented in court in criminal proceedings.

Relevant information can also be used to inform section 47 Enquiries, subsequent civil childcare proceedings or disciplinary proceedings against adults, where allegations have been made.

Visually recorded interviews must be planned and conducted jointly by trained police officers and social workers in accordance with the Achieving Best Evidence in Criminal Proceedings: Guidance on Vulnerable and Intimidated Witnesses (Home Office 2011). All events up to the time of the video interview must be fully recorded.

Parents and, on occasion, children may wish to make representations or complain in respect of one or more of the following aspects of the functioning of child protection conferences:

- The process of the conference.

- The outcome, in terms of the fact of and/or the category of primary concern at the time the child became the subject of a child protection plan.

- A decision for the child to become, to continue or not to become, the subject of a child protection plan.

Complaints should be addressed to the conference Chair who will liaise with the appropriate local authority staff.

All parties must be made aware that:

- this complaints process cannot itself change the decision to have a Child Protection Plan

- during the course of the complaints process, the decision made by the conference stands.

The end result for a complainant will be either that

- a conference is re-convened under a different conference chair

- a Review Conference is brought forward

- it confirms the status quo.

Complaints about individual agencies, their performance and provision (or non-provision) of services should be responded to in accordance with the relevant agency's ordinary complaints handling processes. The safeguarding organisations will have a process to manage complaints about the above aspects of the Child Protection Conference and details about the process should be made available to parents/carers and children and young people.

Any professional/agency who becomes aware that a child who is subject to a child protection plan is missing must inform the lead social worker/manager and agency designated/lead practitioner immediately.

Also see regional procedure on Children missing from care, home and education.

The lead social worker/manager must immediately:

- consult with the police regarding what action should be taken to share information about the missing child – this should include an assessment of whether to release information to the media

- consider all family contacts and those of any other significant adults, including whether the child or their family has links to other areas in the UK

- inform the emergency duty team

- consider whether legal advice is needed

- consider contacting the benefits agency, who are authorised to disclose information from their records

- notify other local authorities according to degree of concern

- consult the child protection conference Chair, who will consider whether the next child protection review conference should be brought forward to consider whether any other action should be taken.

On receipt of a notification from another local authority, a flag should be added to the electronic record system for children’s social care and notification sent to health and other relevant partners.

The adult safeguarding duties under the Care Act 2014 apply to an adult, aged 18 or over, who:

- has needs for care and support (whether or not the local authority is meeting any of those needs)

- is experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect

- as a result of those care and support needs is unable to protect themselves from either the risk of, or the experience of abuse or neglect.

The purpose of reviews of serious child safeguarding cases, at both local and national level, is to identify improvements to be made to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. Learning is relevant locally, but it has a wider importance for all practitioners working with children and families and for the government and policymakers. Understanding whether there are systemic issues, and whether and how policy and practice need to change, is critical to the system being dynamic and self-improving.

Reviews should seek to prevent or reduce the risk of recurrence of similar incidents. They are not conducted to hold individuals, organisations or agencies to account, as there are other processes for that purpose, including through employment law and disciplinary procedures, professional regulation and, in exceptional cases, criminal proceedings. These processes may be carried out alongside reviews or at a later stage. Employers should consider whether any disciplinary action should be taken against practitioners whose conduct and/or practice falls below acceptable standards and should refer to their regulatory body as appropriate.

The responsibility for how the system learns the lessons from serious child safeguarding incidents lies at a national level with the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel (the Panel) and at local level with the safeguarding partners.

The Panel is responsible for identifying and overseeing the review of serious child safeguarding cases which, in its view, raise issues that are complex or of national importance. The Panel should also maintain oversight of the system of national and local reviews and how effectively it is operating.

Locally, safeguarding partners must make arrangements to identify and review serious child safeguarding cases which, in their view, raise issues of importance in relation to their area. They must commission and oversee the review of those cases, where they consider it appropriate for a review to be undertaken.

16C(1) of the Children Act 2004 (as amended by the Children and Social Work Act 2017) states: Where a local authority in England knows or suspects that a child has been abused or neglected, the local authority must notify the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel if – (a) the child dies or is seriously harmed in the local authority’s area, or (b) while normally resident in the local authority’s area, the child dies or is seriously harmed outside England.

The local authority must notify any event that meets the above criteria to the Panel. They should do so within five working days of becoming aware that the incident has occurred. The local authority should also report the event to the safeguarding partners in their area (and in other areas if appropriate) within five working days.

The local authority must also notify the Secretary of State and Ofsted where a looked after child has died, whether or not abuse or neglect is known or suspected.

The duty to notify events to the Panel rests with the local authority. Others who have functions relating to children81 should inform the safeguarding partners of any incident which they think should be considered for a child safeguarding practice review. The link to the Child Safeguarding Online Notification form for local authorities to notify incidents to the Panel is available from Report a serious child safeguarding incident page on Gov.uk.

When a serious incident becomes known to the safeguarding partners, they must consider whether the case meets the criteria for a local review. Meeting the criteria does not mean that safeguarding partners must automatically carry out a local child safeguarding practice review. It is for them to determine whether a review is appropriate, taking into account that the overall purpose of a review is to identify improvements to practice. Issues might appear to be the same in some child safeguarding cases but reasons for actions and behaviours may be different and so there may be different learning to be gained from similar cases. Decisions on whether to undertake reviews should be made transparently and the rationale communicated appropriately, including to families.

The safeguarding partners should promptly undertake a rapid review of the case, in line with any guidance published by the Panel. The aim of this rapid review is to enable safeguarding partners to:

- gather the facts about the case, as far as they can be readily established at the time

- discuss whether there is any immediate action needed to ensure children’s safety and share any learning appropriately

- consider the potential for identifying improvements to safeguard and promote the welfare of children

- decide what steps they should take next, including whether or not to undertake a child safeguarding practice review.

As soon as the rapid review is complete, the safeguarding partners should send a copy to the Panel. They should also share with the Panel their decision about whether a local child safeguarding practice review is appropriate, or whether they think the case may raise issues which are complex or of national importance such that a national review may be appropriate. They may also do this if, during the course of a local child safeguarding practice review, new information comes to light which suggests that a national review may be appropriate. As soon as they have determined that a local review will be carried out, they should inform the Panel, Ofsted and DfE, including the name of any reviewer they have commissioned.

Local Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews: Regional Framework and Practice Guidance

Where a child or young person is the subject of a Child Protection Plan, is in receipt of Child in Need services or there are existing safeguarding concerns whereby any form of assessment or enquiry is ongoing, then should the child be taken abroad agencies should share information as appropriate with the children social care authorities within that country. This will normally be done via the Local Authority Children Social Care responsible for the Child Protection Plan, delivery of services or completion of the assessment/enquiries.

Similarly, if any agency holds concerns that an adult or adults may pose a risk of harm to children, and they believe that the adult(s) have access to, or contact with children or young people who live abroad, whether that be as part of their own family or through a position of trust, then agencies should share information as appropriate with the children social care authorities within that country. This will normally be done via the Local Authority Children Social Care in which the adult(s) reside, but may also be done via the local Police Offender Management processes. The need to share such information, and the extent to which information is shared should be a decision made on a cases by case basis, and that decision and rationale should be documented. Where the need to share information with authorities abroad is being made as a result of that adult occupying a position of trust, then the Local Authority Designated Officer should be involved in those discussions and decision making.

Guidance on what policies and procedures after-school club providers should have in place for:

- health and safety

- safeguarding and child protection

- staff suitability

- governance

After-school clubs, community activities and tuition: safeguarding guidance for providers